How Kubernetes works

Reference link How Kubernetes works | Cloud Native Computing Foundation (cncf.io)

Enter Kubernetes, a container orchestration system – a way to manage the lifecycle of containerized applications across an entire fleet. It’s a sort of meta-process that grants the ability to automate the deployment and scaling of several containers at once. Several containers running the same application are grouped together. These containers act as replicas, and serve to load balance incoming requests. A container orchestrator, then, supervises these groups, ensuring that they are operating correctly.

A container orchestrator is essentially an administrator in charge of operating a fleet of containerized applications. If a container needs to be restarted or acquire more resources, the orchestrator takes care of it for you.

That’s a fairly broad outline of how most container orchestrators work. Let’s take a deeper look at all the specific components of Kubernetes that make this happen.

Kubernetes terminology and architecture

Kubernetes introduces a lot of vocabulary to describe how your application is organized. We’ll start from the smallest layer and work our way up.

Pods

A Kubernetes pod is a group of containers, and is the smallest unit that Kubernetes administers. Pods have a single IP address that is applied to every container within the pod. Containers in a pod share the same resources such as memory and storage. This allows the individual Linux containers inside a pod to be treated collectively as a single application, as if all the containerized processes were running together on the same host in more traditional workloads. It’s quite common to have a pod with only a single container, when the application or service is a single process that needs to run. But when things get more complicated, and multiple processes need to work together using the same shared data volumes for correct operation, multi-container pods ease deployment configuration compared to setting up shared resources between containers on your own.

For example, if you were working on an image-processing service that created GIFs, one pod might have several containers working together to resize images. The primary container might be running the non-blocking microservice application taking in requests, and then one or more auxiliary (side-car) containers running batched background processes or cleaning up data artifacts in the storage volume as part of managing overall application performance.

Deployments

Kubernetes deployments define the scale at which you want to run your application by letting you set the details of how you would like pods replicated on your Kubernetes nodes. Deployments describe the number of desired identical pod replicas to run and the preferred update strategy used when updating the deployment. Kubernetes will track pod health, and will remove or add pods as needed to bring your application deployment to the desired state.

Services

The lifetime of an individual pod cannot be relied upon; everything from their IP addresses to their very existence are prone to change. In fact, within the DevOps community, there’s the notion of treating servers as either “pets” or “cattle.” A pet is something you take special care of, whereas cows are viewed as somewhat more expendable. In the same vein, Kubernetes doesn’t treat its pods as unique, long-running instances; if a pod encounters an issue and dies, it’s Kubernetes’ job to replace it so that the application doesn’t experience any downtime.

A service is an abstraction over the pods, and essentially, the only interface the various application consumers interact with. As pods are replaced, their internal names and IPs might change. A service exposes a single machine name or IP address mapped to pods whose underlying names and numbers are unreliable. A service ensures that, to the outside network, everything appears to be unchanged.

Nodes

A Kubernetes node manages and runs pods; it’s the machine (whether virtualized or physical) that performs the given work. Just as pods collect individual containers that operate together, a node collects entire pods that function together. When you’re operating at scale, you want to be able to hand work over to a node whose pods are free to take it.

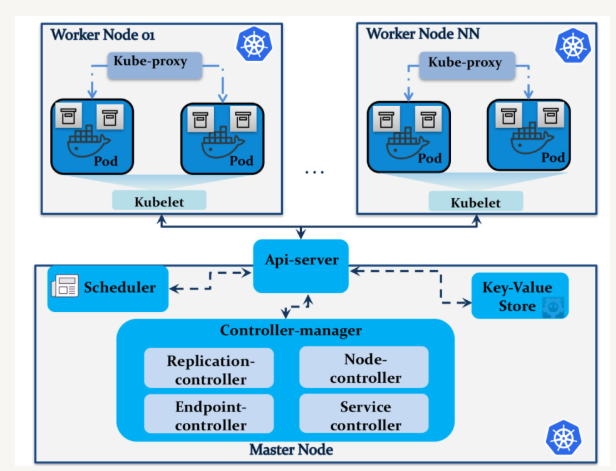

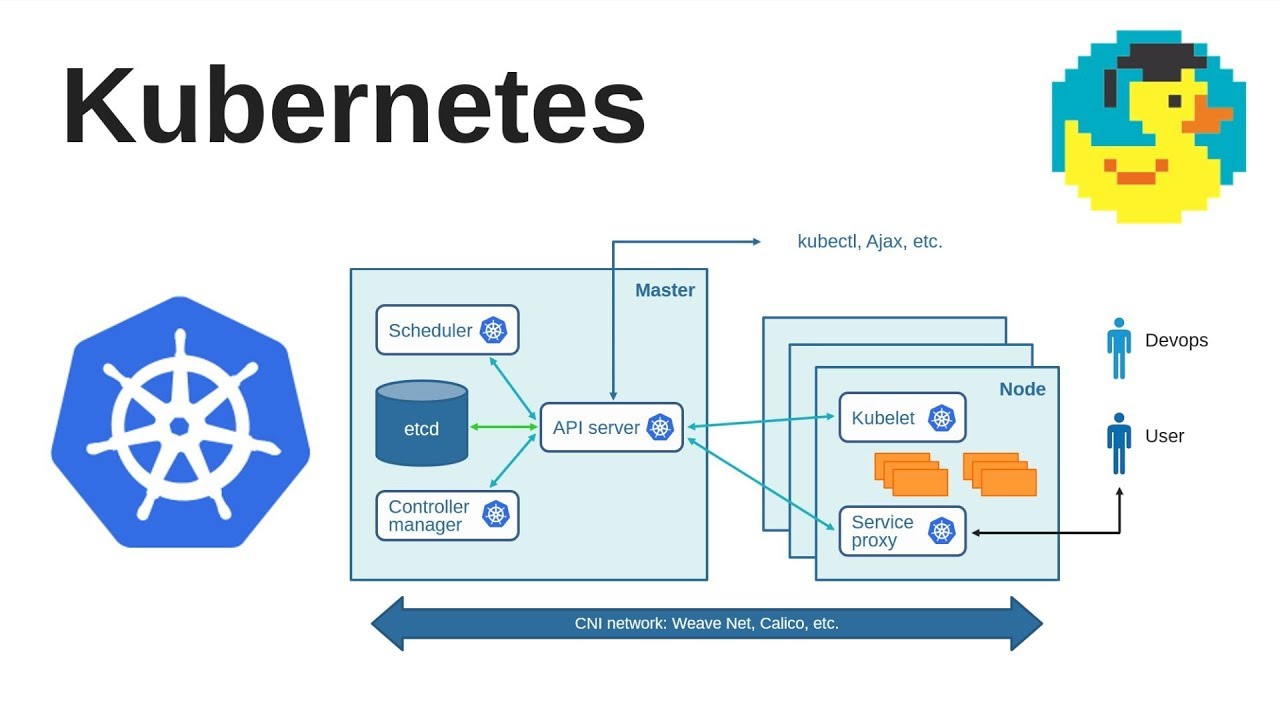

The Kubernetes control plane

The Kubernetes control plane is the main entry point for administrators and users to manage the various nodes. Operations are issued to it either through HTTP calls or connecting to the machine and running command-line scripts. As the name implies, it controls how Kubernetes interacts with your applications.

Cluster

A cluster is all of the above components put together as a single unit.

Kubernetes components

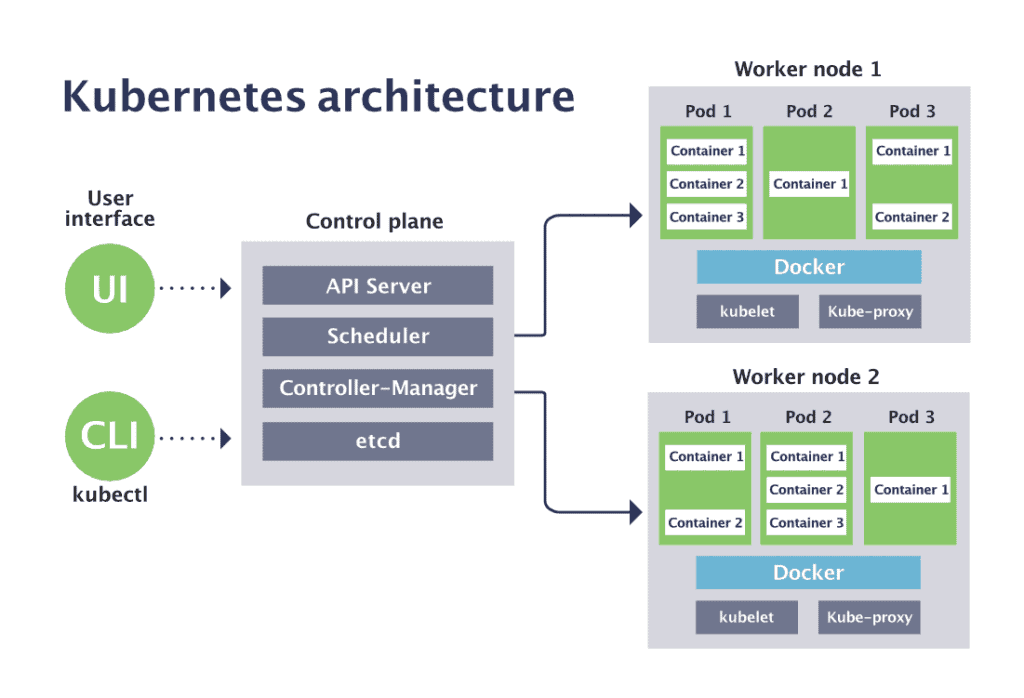

With a general idea of how Kubernetes is assembled, it’s time to take a look at the various software components that make sure everything runs smoothly. Both the control plane and individual worker nodes have three main components each.

Control Plane

API Server

The API server exposes a REST interface to the Kubernetes cluster. All operations against pods, services, and so forth, are executed programmatically by communicating with the endpoints provided by it.

Scheduler

The scheduler is responsible for assigning work to the various nodes. It keeps watch over the resource capacity and ensures that a worker node’s performance is within an appropriate threshold.

Controller manager

The controller-manager is responsible for making sure that the shared state of the cluster is operating as expected. More accurately, the controller manager oversees various controllers which respond to events (e.g., if a node goes down).

Worker node components

Kubelet

A Kubelet tracks the state of a pod to ensure that all the containers are running. It provides a heartbeat message every few seconds to the control plane. If a replication controller does not receive that message, the node is marked as unhealthy.

Kube proxy

The Kube proxy routes traffic coming into a node from the service. It forwards requests for work to the correct containers.

etcd

is a distributed key-value store that Kubernetes uses to share information about the overall state of a cluster. Additionally, nodes can refer to the global configuration data stored there to set themselves up whenever they are regenerated.

Recent Comments